From a profile in the New York Times, April 27, 1997

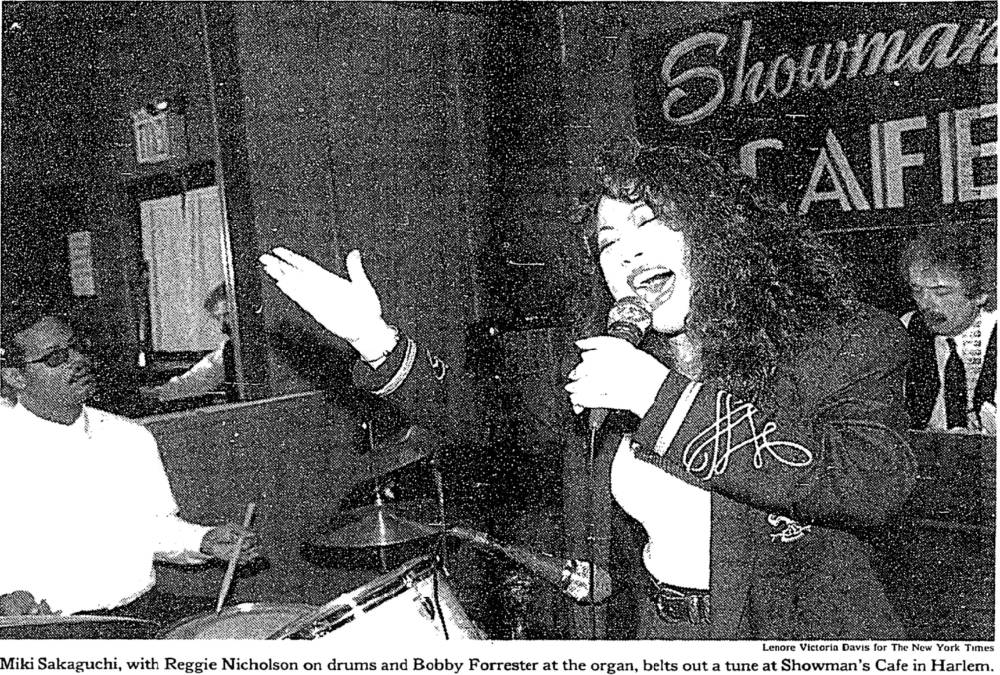

IT was pushing 11 P.M. on a recent Wednesday, and the Bobby Forrester Trio was gearing up for its second set at Showman’s Cafe in Harlem. Miki Sakaguchi, the evening’s featured performer, stopped by a table to greet a handful of Japanese tourists who had trickled in from Amateur Night at the Apollo Theater.

”Did you enjoy the performance?” she asked in soft, staccato Japanese. ”I hope you enjoy my show, too.”

Presently, Bill Saxton, the jazz trio’s saxophonist, bellowed: ”Let’s put your hands together for a warm Harlem applause for Miki Sakaguchi.”

Smiling broadly, Ms. Sakaguchi, in a flowing black jacket and matching pumps, began singing ”All Of Me.”

”All of me, why not take all of me,” she coos into the microphone, gently grimacing, hands clapping, shoulders swaying. ”Can’t you see I’m no good without you . . .”

After a round of applause, the regulars at the bar returned to their drinks and their conversations. But the tourists remained transfixed by Ms. Sakaguchi, a compatriot who had achieved a measure of success in an American musical mecca.

Her name may draw a blank to music lovers at large, but here in Harlem — and in Japan — Ms. Sakaguchi, affectionately known as ”Soul Sister Miki,” gained renown with an eclectic repertoire of Top 40 pop, Tin Pan Alley favorites, gospel, and soul, jazz and blues standards, with an occasional traditional Japanese folk song thrown in.

In addition to her regular Wednesday night gig at Showman’s, Ms. Sakaguchi has also performed at the fabled Cotton Club and at the amateur night at Apollo theater, where against all odds, she took first place twice and finished a respectable fourth at the Super Top Dog contest, the annual competition of the year’s best. One of her highest achievements came two weeks ago when she sang ”The Lord’s Prayer,” a gospel song, at a Red Cross benefit that featured prominent musicians like the jazz singer Ruth Brown and the saxophonist Lonnie Youngblood at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

Over the years, Ms. Sakaguchi, 36, has gained a following in Harlem and she has been a draw among some of the 500,000 Japanese tourists who visit New York annually. But her success has made some people uneasy. Reluctant to sully the international spirit that has brought more tourism to Harlem, none of her critics wanted their names used. Privately, they say she has been given an unfair advantage over local talent and that her style lacks passion.

But Ms. Sakaguchi’s supporters are eager to point out her contributions. She lives with her partner, Toshiaki (Tommy) Tomita, in Harlem, where she sings in the choir at St. Stephen’s Community A.M.E. Church, performs for the elderly and promotes the neighborhood as a tourist attraction in her weekly radio show, which is broadcast in Japan. They say her success is a testament to the harmony that can be achieved through cultural exchange.

”Miki just shows you that there are certain things that transcend race and financial background,” said a longtime friend, Melba Wilson, a partner in Minton’s Playhouse, a jazz club soon to reopen in the Cecil Hotel, on 118th Street and St. Nicholas Avenue. ”She allows us to see that we are all the same, that we all love the Lord, that we need to embrace people who look different and that not all of them are out to get us.”

Ms. Sakaguchi said she learned to love American music from her father, a taxi driver in Tokyo. ”My papa loved jazz and soul music,” she said in halting English. ”I grew up listening to Ella Fitzgerald and Aretha Franklin.”

Driven by the desire to sing, she auditioned for jazz clubs in the trendy Roppongi district in Tokyo after graduating from a junior college. But club owners were not impressed. ”Her voice had promise,” said Mr. Tomita, who owned several jazz clubs in Roppongi at the time and auditioned Ms. Sakaguchi. ”But she just wasn’t ready.” But Ms. Sakaguchi persevered and eventually succeeded in getting small gigs during off-peak hours.

Eager to fulfill his own dream to explore jazz and soul music, Mr. Tomita sold his clubs in Japan in 1985 and spent the next three years frequenting music venues in New Orleans and Chicago before settling in New York. He made friends on the Harlem music scene and established himself as a successful tour guide for Japanese visitors there. He also began to book Harlem musicians for performances in Japan. He sent rave reports about Harlem and its music back to friends in Japan, including Ms. Sakaguchi, whose marriage to a Japanese jazz drummer was falling apart.

”I wanted to come and hear it for myself,” Ms. Sakaguchi said.

Leaving behind a year-old daughter, Ms. Sakaguchi arrived in New York in 1987 and found a job at a SoHo bed-and-breakfast where Mr. Tomita had worked, cooking and cleaning during the day, learning English in the afternoon and going to Harlem jazz clubs at night. The two fell in love.

Through Mr. Tomita, Ms. Sakaguchi met the music producer Bobby Robinson, who discovered Gladys Knight and the Pips, Mr. Youngblood, who gave Jimi Hendrix his start as a guitarist in his band, and LeRoy Myers, who was the business manager for B. B. King. Through their connections, Ms. Sakaguchi began to perform in clubs, often appearing with Mr. Youngblood.

Hoping to cement her reputation locally, Ms. Sakaguchi in 1991 performed at Amateur Night at the Apollo, well known for an audience brutally honest in its opinions.

”The audience started to boo as soon as they heard the announcer say I was going to sing ‘You Needed Me,’ a slow song,” Ms. Sakaguchi recalled with a hearty chuckle. ”They started booing again when they saw my face.”

Again, she persevered. Ms. Sakaguchi eventually won over the audience with her emotionally charged rendition of ”Dr. Feelgood,” a signature song of Aretha Franklin.

Musicians who have worked with Ms. Sakaguchi attribute her success to her ability to dazzle the audience through a combination of pleasing personality and a unique cultural twist.

”She has her own style,” said Mr. Robinson, the producer. ”She doesn’t sing ‘Dr. Feelgood’ like Aretha, but she brings her own feelings to the song. She’s Miki, not Aretha. She is at the point where she needs to find one song that is her own to put her over.”

| Credit Type | Production | Season |

|---|---|---|

| Actor | Looking Back | 1993-94 Season |